Forza D’Agro’

Forza D’Agro’

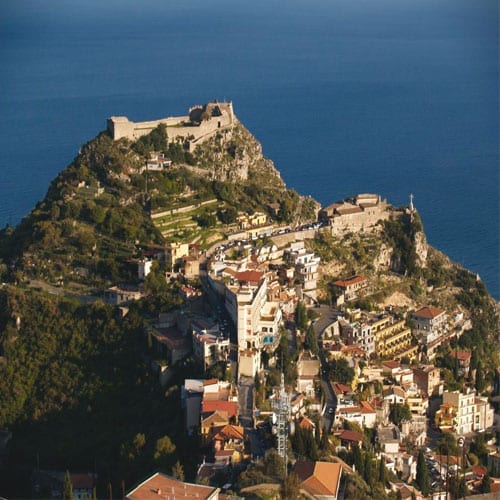

Tra cielo e mare

MUNICIPALITY OF forza d’agro’

(Province di Messina)

Altitude

m. 420 s.l.m.

Population

900 (250 nel borgo)

SAINT patron

SS. Crocifisso, 14 settembre

turisT INFORMATION

Ufficio Informazioni Turistiche

presso il Comune, Piazza Giovanni XXIII, 1;

orari di apertura e chiusura:

martedì, mercoledì e venerdì dalle ore 8.00 alle ore 14.00

lunedì e giovedì dalle ore 8.00 alle ore 18.00

Tel. 0942 721016

E-mail: info@comune.forzadagro.me.it

The name Forza d’Agrò derives from “Fortress” (Latin fortilicium), originally called Fortilicium d’Agrò—literally “Fortress of Agrò”—later shortened to Forza d’Agrò. The second element, Agrò, goes back to the ancient Greek name Ἄrghennon (“silvery”), bestowed by the Greeks upon the promontory of Saint Alexius; over time it became Ἄrgòn, then Agròn, and finally Agrò.

Long before medieval times, around 1000 B.C., the Siculi likely inhabited the hills that now form the territory of today’s Forza d’Agrò. Along the banks of the Agrò valley stood Phoinix, a Phoenician trading port, while above it rose a fortified citadel—variously known as Kallìpolis or Agrilla—which was eventually destroyed. Between the 8th and 5th centuries B.C., Greek colonists settled here, only for the Romans to conquer the area in 135 B.C. Upon Roman rule, the Greek “Agrò” became the Latin Agrylla. From 536 A.D. to 827 A.D., the region fell under Byzantine dominion, during which time Basilian monks of the Greek‑Oriental rite established both the Monastery and the Church of Saints Peter and Paul of Agrò. In the 8th century, repeated Saracen raids culminated in the destruction of that monastery by the Arabs.

With the Norman conquest, Count Roger I is credited with building the Castle of Forza d’Agrò and rebuilding the Monastery of Saints Peter and Paul. A 1117 diploma of King Roger II first mentions the Vicum Agryllae—“village of Agrylla”—nestled on the edge of the Agrò stream. As the population grew and sought greater security, inhabitants gradually moved uphill, first to the district of Casale and later to the town’s present site. In the Magghia district, a quarter emerged on a clearing facing Mount Etna. Around the lofty castle keep—la Guardiola—the picturesque settlement of Quartarello took shape, while the local community, long called the “University of Agrò,” is today the Municipality of Forza d’Agrò.

During the Sicilian Vespers uprising of 1282 against the French, Forza d’Agrò contributed twenty archers to guard the route between Taormina and Messina. It was in the 14th century that the village really began to take the form it still retains, clustered around the castle. After the 1674 revolt—pitting Spaniards against French forces—Forza d’Agrò, loyal to the (defeated) Spanish crown, was treated as conquered land and absorbed by neighboring Savoca, losing the privileges granted by Roger II. In the early 1800s, the British occupied the castle. The town took part in the revolutionary uprisings of 1848, and in the early 20th century many residents emigrated to the Americas. In 1948 the hamlet of Sant’Alessio separated from Forza d’Agrò—although the Scifì locality and the coastal stretch from Capo Sant’Alessio to the Fòndaco Parrino stream remained within its boundaries. Subsequent emigration in the 1950s and ’60s gave way to a period of modernization: new roads, villas, and piazzas were built; important cultural monuments restored; public establishments opened; and the town became a film location for major productions such as The Godfather parts I, II, and III.

Today, Forza d’Agrò’s houses press tightly together along narrow lanes, rising in tall, slender silhouettes. Their sandstone door‑arches feature a variety of keystones, and their lintelled windows are also formed of solid sandstone blocks. Wrought‑iron balconies, supported by shaped corbels, are characteristic, often bearing flowering pots or planters of basil and aloe. The buildings themselves are constructed of local earth and stone, a testament to centuries of living in harmony with the land.

- Chiesa di San Francesco: 16th century – In the 1682 tabernacle above the main altar stood the marble statue of S. Caterina d’Alessandria (now in the Chiesa Madre).

- Arco Durazzesco: in the Catalan‑Gothic style, dating to the late 1400s. It is reached by a theatrical sandstone staircase. Nearby stands the smaller “arco agostinicchiu.”

- Chiesa della SS. Trinità: rebuilt in 1576 on the 15th‑century structure. It belongs to the eponymous Confraternita. Above the main altar is the painting “Abramo nel deserto” (a copy).

- Ex Convento degli Eremiti di S. Agostino con chiostro: dating to 1591, the year the Confraternita granted the church of the Triade to the Augustinian friars.

- Cripta nel convento agostiniano: masonry channels and decorative drawings adorn the small room used for mummification (restored in 2000).

- Piazza Vincenzo Cammareri, dedicated to the distinguished Forza d’Agrò physician who died in 1911; at its center stands a fountain topped by a towered stele.

- Chiesa Madre: dedicated to S. Maria Annunziata e Assunta, in early‑18th‑century Baroque style, rebuilt on the 15th‑century “old church.” Restored in 2001 and rich in artworks.

- Quadro dell’Annunciazione in the Chiesa Madre (early 1500s). An Antonellian work, 2.15 m wide by 2.50 m high, in a majestic 1560 frame.

- Croce dipinta su tavola: the SS. Crocifisso, patron of the town. In the Chiesa Madre, mid‑15th century, anonymous author, 2.15 m × 1.56 m. This miraculous image is carried in procession.

- Coro in noce intagliato in the apse of the Chiesa Madre, 18th century, anonymous: 24 stalls depicting scenes from the lives of the Virgin and of Jesus.

- Case di via Roma: 18th‑century houses of the local aristocracy (Guarnera, Giardina, Quagliata, Miano) adjacent to the 19th‑century Muscolino olive‑mill.

- Casa Crisafulli‑Gussio: 18th century, in Piazza Duomo, notable for its wrap‑around balconies and iron curtain‑rod supports.

- Vicolo delle carceri: roofed by overlying structures, with underground hiding‑and‑defense spaces, and iron‑grilled narrow cells once used as prisons.

- Via SS. Annunziata, with its tall, narrow houses pressed together, distinguished by their small doors and balconies; the main palaces face onto it.

- Palazzo Miano‑Pizzolo: 17th century, on Via SS. Annunziata, distinguished by its balcony supported on broad sandstone corbels with geometric and floral motifs.

- Palazzo Mauro: 17th century, in Via Laino, a grand mass with large lintelled windows and a porch of big corner arches. Next to it lie the remains of an olive press.

- Palazzo Bondì: 17th century, at the start of Via Portello, with a bulging wrought‑iron balcony held by shaped corbels and two elliptical sandstone windows.

- Palazzo Garufi‑Schipilliti: 17th century, refurbished in 1771, in Via SS. Annunziata. Originally included finely decorated rooms plus wine‑press, cellar, and oil store.

- Piazza Pasquale Carullo, a true “terrace over the Strait of Messina,” from which you can admire August meteors on warm summer nights.

- Chiesa di S. Antonio Abate: 16th century, at the edge of the borgo, with a carved sandstone portal. Today it houses the Museo d’Arte Sacra.

- Rocca: neighborhood of houses built on rock, featuring the round “u tunnu” piazzetta with panoramic views and a circular bench perfect for group chats.

- Quartarello, a borgo with a typical medieval layout, clinging to the castle’s cliff, with zig‑zag alleys, stone stairways, and tile‑roofed houses.

- Casetta cinquecentesca al Quartarello, with its entrance door framed by projecting moldings and anthropomorphic corbels supporting the flower‑laden balcony.

- Castello normanno, traditionally built by Count Roger in the 11th century, with a bell‑tower and walls pierced by loopholes. Restored in 1595.

- Guardiola del Castello: standing a stone’s throw from the fortress, this massive defensive tower, complete with loopholes, dominates the horizon.

- Magghia, ancient borgo. Its rock‑perched houses press along narrow lanes. Noteworthy is the painting of the Almighty in the Chiesa di S. Sebastiano.

- Palmenti rupestri: rock‑hewn and rural wine‑presses in the Forza countryside, with wide, deep vats on two levels for grape‑treading and must collection.

- Aie, in the windy countryside: a round, leveled ground ringed with stones, used for threshing.

- Macigni “mammellonati” with caves carved by weathering, long used as hermitages or shelters.

- Monte Rocca Scala: narrow lanes and steep stone staircases protected by sandstone blocks, winding between the Forza countryside, Santoleo, and Recavallo.

Ville Comunali “G. Falcone” e “D. Lombardo”, terraces with flowerbeds, trees, and fountains, overlooking the Strait of Messina, Calabria, and the Bay of Taormina.

Game and fish—but also lamb, beef, and pork—are the stars of second courses in Forza d’Agrò, beloved by locals and visitors alike who choose the village for a peaceful getaway.

Signature dishes include coniglio all’agrodolce (sweet and sour rabbit), braciole alla messinese (Messina-style meat rolls), salsiccia col finocchietto arrostita (grilled sausage with wild fennel), stoccafisso “a ghiòtta” (stockfish stew), and sarde “a beccafico” (stuffed sardines). These traditional mains are perfectly paired with homemade maccheroni al sugo, all generously accompanied by the bold, rustic notes of the local red wine. Around the table, it’s not unusual to find a colorful spread of appetizers and side dishes—eggplants, peppers preserved in oil, white and black olives, sun-dried tomatoes—each one echoing the genuine spirit of Sicilian hospitality.

Fish, always fresh, is prepared with care by local chefs who honor recipes passed down through generations. Fragrances and flavors here are exactly as they once were—simple, rich, unforgettable.

And when the sun turns up the heat, refreshment arrives in a glass or on a spoon: under the shade of vine-covered pergolas, locals and visitors cool off with a classic lemon granita or a caffè con panna e brioche, expertly prepared by village baristas. The result? A sweet pause, rich in flavor and in tradition.

But it’s not just the cuisine that speaks of heritage—the very land of Forza d’Agrò tells a story. Today, the village’s most prized products come from its fields: olive oil and wine, cultivated with the same care and wisdom that defined this area for centuries.

Since Roman times, wines from the Taormina region were among the most celebrated in the ancient world—prized, traded, and enjoyed far beyond Sicily’s shores. Scattered through the countryside of Forza d’Agrò are silent witnesses to this history: palmenti (stone wine presses), both rock-hewn and rural, still standing amidst the olive trees and vines.

Even in 19th-century travel guides, Forza d’Agrò was noted for its exports of oil and silk. One guide even remarked, “Its primary export trade consists of oil and silk. The air is healthy.” The silk, once produced from local silkworms, now lives on only in the memories of the village elders, but its legacy remains—woven into the soul of a place where nature, tradition, and authenticity continue to thrive.

Festa del SS. Crocifisso: Held on September 14th, this celebration honors the town’s patron saint. As the faithful cry out “E chiamàmulu sempri ‘o spissu! Evviva lu Santissimu Crucifissu!”, the miraculous image is carried through the streets in a moving procession, embodying the community’s deep devotion and spiritual heritage.

Festa della SS. Trinità: Celebrated during odd-numbered years, either on the official feast day or in the summer, this event is marked by a solemn yet joyful encounter between the Confraternities of Forza d’Agrò and Gallodoro. Their banners are ceremonially kissed, and traditional cuddure—ring-shaped breads baked in the centuries-old Triade oven—are distributed as tokens of fraternity and celebration.

Festa dell’alloro: Taking place on Easter Monday, this tradition features a procession of the Sacred Oils and laurel banners crafted by the town’s youth. The laurel is blessed, and cuddure are once again handed out, treasured in homes as symbols of good luck and protection throughout the year.

Distribuzione delle cuddure: These small, symbolic dough rings are made in the historic Triade oven and offered during the celebrations of the SS. Trinità and Alloro. Families keep them at home as a sign of well-being and spiritual safeguarding.

Presepe vivente: On the day after Christmas, the medieval streets of Forza d’Agrò are transformed into a living nativity scene. Visitors are immersed in scenes from Bethlehem, complete with reenactments of ancient trades, traditional music played by zampognari (bagpipers), and tastings of typical local products.

Vini In-chiostro: This elegant wine tasting event takes place in July within the cloister of the Augustinian convent. With the participation of professional sommeliers and renowned wineries, guests are guided through a sensory journey of refined local and regional wines.

Premio “Borgo fiorito”: This friendly contest invites residents to decorate balconies, windows, and alleyways with vibrant flowers, adding charm and color to the village and offering visitors a more welcoming and picturesque experience.

Ottobrata forzese: Every Sunday in October, Piazza Giovanni XXIII comes alive with food and craft stands during this festive market. People from neighboring towns flock to the village to enjoy handmade products and traditional dishes in a joyful, community-driven atmosphere.

Gemellaggio tra i Comuni di Forza d’Agrò e Marktoberdorf: This twinning pact celebrates the strong bond between Forza d’Agrò and the German town of Marktoberdorf, where many forzesi were born or once worked. Regular exchanges and visits foster a spirit of brotherhood, cultural exchange, and shared memories.

The hilly territory of Forza d’Agrò is perfect for hiking, cycling, or horseback riding, offering a direct and immersive contact with nature. The air is so clear and bright that photography enthusiasts can capture breathtaking views of the vast sea and mountain horizons, as well as the local flowers and plants that color the landscape.

You can stroll along special trails scattered throughout the Forza countryside. These paths reveal unforgettable panoramas and natural scenes just waiting to be admired and photographed. Thanks to the efforts of the “Gruppo Volontari Sentieri” (Volunteer Trail Group), old mule tracks and paths once traveled by farmers on foot or donkey back have been restored.

Now, you can explore routes like the trail from Vignàle to Monte Recavallo, passing through the Rocche a Scala, or the path leading to the Church of Saints Peter and Paul of Agrò (now part of the Casalvecchio municipality), which crosses the ancient washhouse of Canale and the archaeological digs of Scifì. The association has also rediscovered the Forza d’Agrò–Taormina trail and the Forza d’Agrò–Fòndaco Prete path, which leads down to the sea at Forza d’Agrò.

Here and there, old farmhouses and abandoned wine presses (palmenti) peek through the landscape. From the heights, you can enjoy a unique panorama stretching from the Strait of Messina’s sparkling waters all the way to the snowy, smoking summit of Mount Etna.